In the 1840s, echoes of a new sound emerged from Maine’s forests: the rhythmic bang of hammers striking upon granite and iron. Within a few years, the promise of progress had reached the northernmost corner of Maine and other northern New England States. Portland’s merchants dreamed of an economic lifeline tethering their city to the Canadian interior, a rail artery stretching from their Atlantic port to Montreal. Out of that ambition came the Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad, a venture that would carve through forests, mountains, crossing rivers, and, most enduringly, be made in the blood, sweat, and lives of immigrant labor.

When construction began in 1846, Maine’s labor market was unprepared for the scale of the task at hand. It was said that local men, such as the farm laborers and tradesmen, were seemingly unwilling to endure the brutal, backbreaking manual labor required by the work. The company’s leaders, however, quickly identified where to look to fill the much-needed labor force.

Across the Atlantic, the tragedy of the Great Hunger (An Gorta Mór) was unfolding. Beginning in 1845, a devastating potato disease swept through Ireland, destroying the staple food crop for the vast majority of the people. Governmental response was delayed, inefficient, and substandard, thereby intensifying the people’s suffering and deaths. Over one million people died of starvation and disease, and millions more were forced to flee their country to survive.1 The Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad actively capitalized on this desperation. Ships arrived in ports like Boston, Portland, and Saint John carrying the poor, half-starved, and weakened masses of Irish souls escaping the calamity in their homeland.

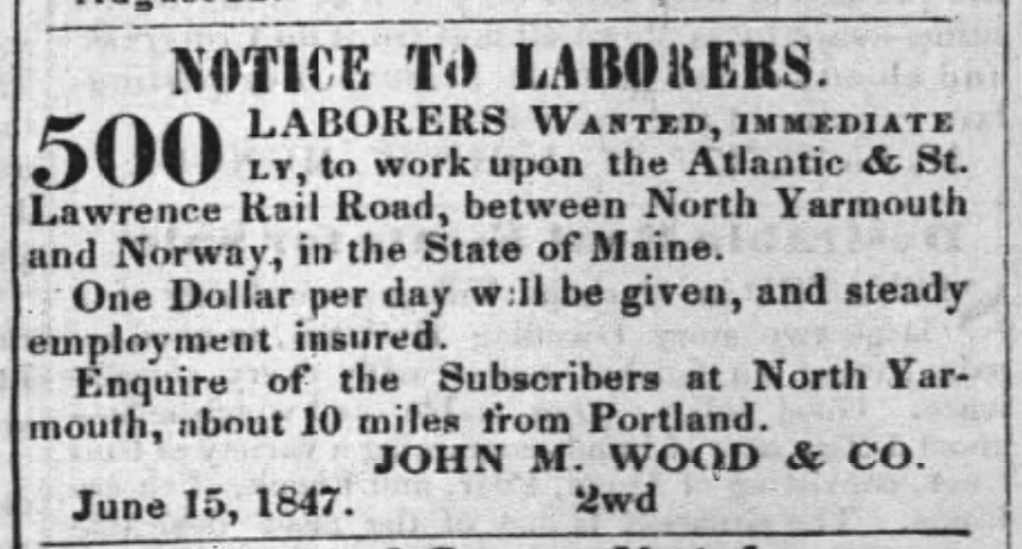

Old newspapers, including ones published in Ireland, carried recruitment advertisements, calling for hundreds of laborers to work on the American railroad. For those advertisements in Ireland’s papers, a promise of a dollar a day and sponsored ship passage in exchange for a year’s employment commitment was enticing. Destitute, desperate, and determined, Irishmen answered this call, picking up the shovels and picks to earn a meager wage and with a dream of a better life in a new land. The terms of their employment were exploitative. Irish immigrants dug, blasted, and pushed their way northward from Portland to Montreal. The average daily wage for this dangerous labor was often less than a dollar, with most rates falling between 75 and 90 cents. Company deductions for the cost of food, clothing, and rudimentary lodging in company-owned shanties may have further reduced their meager compensation. The work was considered so dangerous that a grim saying about railroad construction emerged, something like, “There’s an Irishman buried under every railroad tie.”

The laborers cut deep into Maine’s forests, granite hills and ridges, and bridged the rivers. Diseases, such as cholera, spread easily in their work camps, where sanitation was minimal or nonexistent. Accidents, however, were the most immediate and looming threat. Black powder explosions were unpredictable; a single mis-timed fuse or loose stone sent deadly fragments flying about and in unexpected directions, maiming or killing workers. Workers fell from or were smothered by collapsing embankments. They were crushed by the cars and wagons hauling loads or fill. They sometimes lost a leg, an arm, fingers, a foot, or their eyesight. The human cost of this “progress” may never be fully understood, as records of accidents and fatalities are scant. Company records and local newspapers rarely included the names of the dead and injured. Irish laborers’ families may have received no official notice of their fate. The danger was not confined to the remote wilderness; tragedy struck within the city of Portland, too, demonstrating that the constant, lethal peril faced by these workers was real and it was everywhere.

Here is a small list of accidents and deaths and their locations, as mentioned in local newspapers, to illustrate the dangers faced by Irish railroad laborers, named and unnamed, working in the state of Maine:

- Bath: In 1849, Thomas Caron, an Irish railroad laborer, was run over by a gravel train. 2

- Bethel: In 1851, an Irish railroad laborer slipped off a gravel train, jamming both of his legs, killing him.3

- Cumberland: On August 25th, 1850, a railroad incident killed several laborers and mangled several more.4 While the news account did not provide their identities or ethnicities, a quick search for city and state death records for the accident date, which includes a cause of death as a casualty, produced names of three possible victims: Matthew Haley5, Jeremiah O’Brien6, and Jerry Breslin7.

- Danville: In 1847, Patrick Conley, an Irish railroad laborer, froze to death.8 In 1847, Patrick Masterson, an Irish railroad laborer, was killed by the collapse of an earthen embankment.9

- Falmouth: In 1847, John Barrett, an Irish railroad laborer, was killed almost instantly in an accident at the railroad bridge on the Presumpscot River.10

- Gardiner: In 1850, James Cahill, an Irish railroad laborer, was killed by the collapse of an earthen embankment.11

- Gorham: In 1852, Patrick Ryan, an Irish railroad laborer, fell off the top of a moving train, falling onto the rails, and then the train ran over his leg, killing him.12

- Orono: 1853, Timothy Crowley, 28, killed instantly by the collapse of an earthen embankment while working on the railroad.13

- Paris: In 1850, Thomas Foley, an Irish railroad laborer, died as a result of blasting rock about eight miles above the town.14

- Portland: In 1847, some Irishmen excavating dirt on the city’s railroad track were injured. One, named Smith, broke several ribs.15 In 1847, Patrick Tumy, an Irish railroad laborer, broke his leg while loading stone on a wagon.16 In 1853, an Irish railroad laborer was killed by being jammed between two gravel cars.17

By the end of 1853, the Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad line was complete, and it eventually became part of the Grand Trunk Railway system. The line connected Portland to Montreal, creating a vital link between New England’s seaports and Canada’s trade routes, transforming Portland into a bustling port city and driving even more economic growth across industries that benefited from or supported this new line.

Yet thousands of Irish laborers who built the tracks are nameless, and some of the names recorded in the 1850 Maine US census, for example, seem to have vanished. Their sacrifices, found in their broken bodies, lost lives, and shattered families, were rarely recorded with the same care as the company’s accomplishments and its profits. Some of the surviving laborers may have moved on to other railroad sites, while others may have secured different employment, such as in the mills. In some cases, laborers who were permanently disabled by their injuries were unable to work, leaving them financially dependent on their families or friends, or they might have ended up in the city’s almshouse. Few of their identities were preserved; fewer still remembered. But remnants of their hard work, the iron rail bridges and their stone foundations, and the miles and miles of rail track still stretching along the old route to Canada, endure as a testament to their existence and the incredible sacrifices they made to tie our two countries and economies together.

Do you have an Irish immigrant ancestor who helped build the Maine railroad system in the mid-19th century? Do share their story in a comment, or send a pm.

Thank you for reading this story.

♥︎ Krista

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Notes

- Miller, Kerby A, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America. Oxford University Press, 1985. ↩︎

- “Railroad Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Mon, July 16, 1849. ↩︎

- “Portland, 7th” The Weekly Mercury (Bangor, Me), Tue, October 14, 1851. ↩︎

- “Shocking Railroad Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Mon, August 26, 1850. ↩︎

- “Maine, U.S., Death Records, 1761-1922,” death certificate for Matthew Haley, August 25, 1850, Cumberland County, Maine, Maine State Archives, Augusta; digital image, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com (accessed July 2, 2025). ↩︎

- Maine, U.S., Death Records, 1761–1922,” entry for Jeremiah O’Brien, died August 25, 1850, Cumberland County, Maine; Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed July 2, 2025). ↩︎

- Maine, U.S., Death Records, 1761–1922,” entry for Jeremiah O’Brien, died August 25, 1850, Cumberland County, Maine; Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed July 2, 2025). ↩︎

- “Froze to Death” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Thur, February 25, 1847. ↩︎

- “Fatal Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Tue, February 16, 1847. ↩︎

- “Fatal Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Sat, December 18, 1847. ↩︎

- “Fatal Accident” Portland, Press Herald (Portland, Me), Fri, February 8, 1850. ↩︎

- “Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Fri, December 24, 1852. ↩︎

- “Fatal” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Mon, March 14, 1853. ↩︎

- “Accidental Death” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Sat, August 10, 1850. ↩︎

- “Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Thur, February 11, 1847. ↩︎

- “Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Thur, July 8, 1847. ↩︎

- “Accident” Portland Press Herald (Portland, Me), Tue, November 29, 1853. ↩︎

Leave a comment