I’ve been involved in DNA testing for genealogical purposes since early 2012,1 and over the years, I’ve tested both autosomal DNA (aDNA) and Full mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) through a testing company called FamilyTreeDNA (FTDNA). Before I share this story, I want to be upfront. I have no affiliation with FTDNA and receive nothing for mentioning them. I’m simply a Family Historian sharing an experience I hope might be encouraging for others who are curious about their family history.

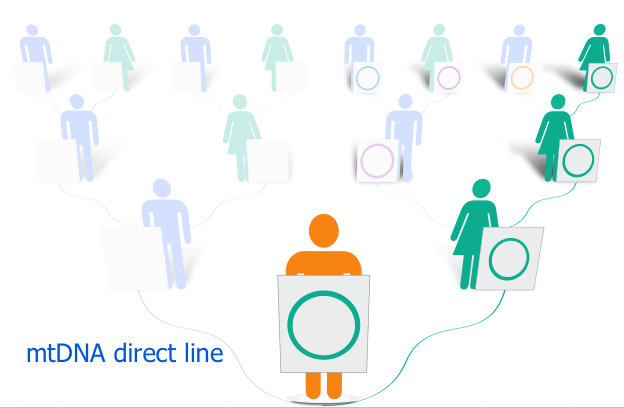

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited only through the maternal line. A person inherits it from their mother, who passes it down to all her children, but only the daughters will pass it down. It’s a singular straight line of inheritance. Last year, FTDNA updated its mitochondrial family tree, and with the update came a small change. My haplogroup designation shifted from J1c3g to J1c3g22. It was a minor tweak, but it revealed a match buried among dozens of others. With the new designation came my first-ever potentially viable full mtDNA match, and so far, a lone one at J1c3g22. According to FTDNA, this person and I share a common motherline ancestor who lived approximately 500 years ago, give or take a few centuries. That’s a long time ago, but little did I know the story would get closer to home.

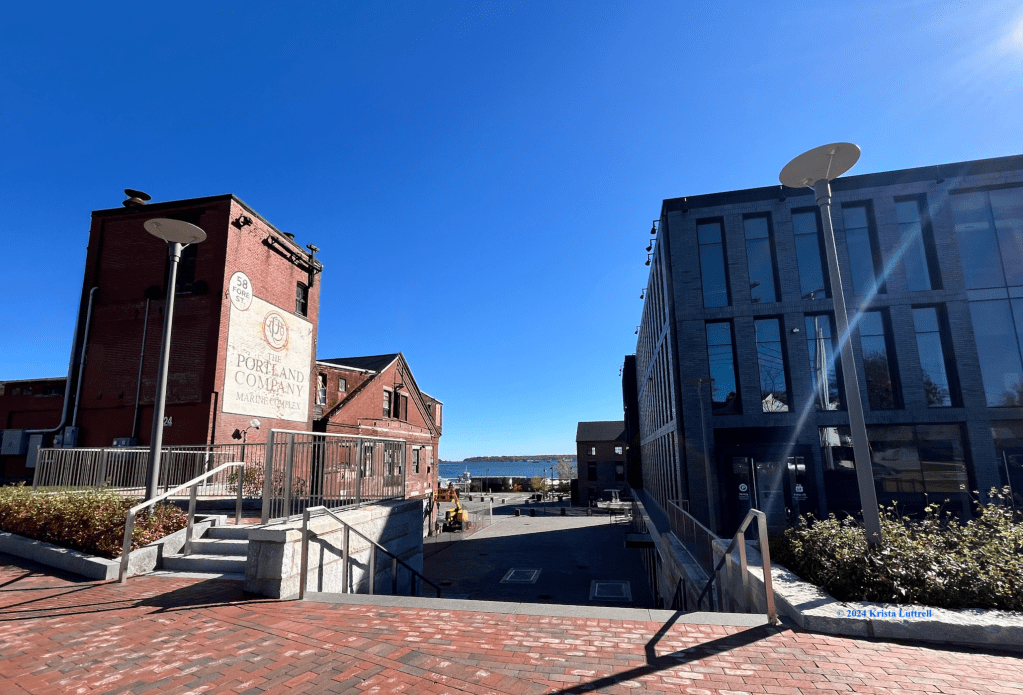

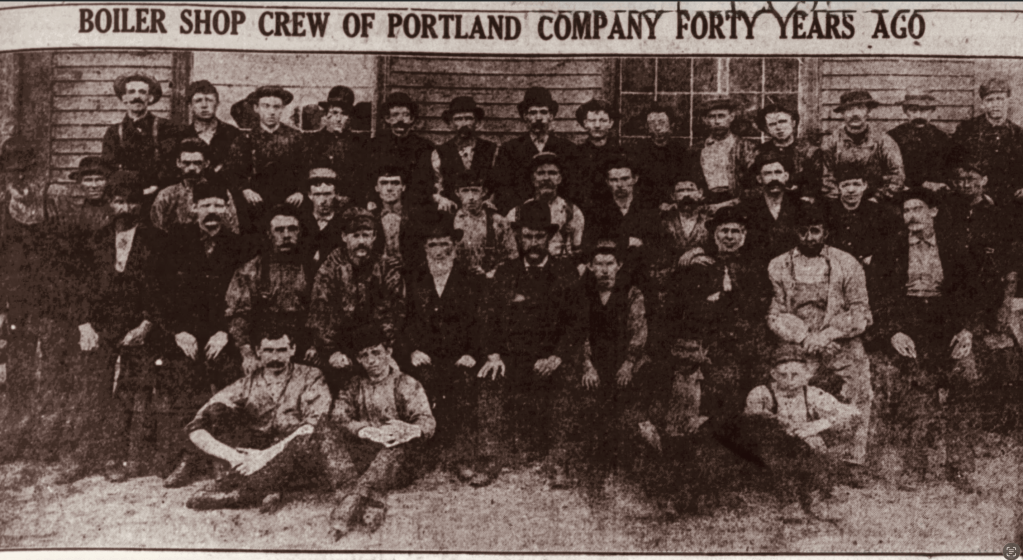

Digging into the match, I found that their most distantly known maternal ancestor lived in the parish of Belclare, County Galway, Ireland, which is the same parish of origin as my most distantly known maternal ancestor. They lived only a few miles apart. My maternal ancestor left Ireland in the 1850s and settled in Portland, Maine. The maternal ancestor of my match emigrated to Lowell, Massachusetts, some decades later. It’s only about an hour’s drive from Portland to Lowell.

The townlands where our ancestors lived were fairly close. It is possible they may have met or known each other, and yet been totally unaware of their ancestral connection. It may not be documented proof of a shared family, but knowing that our ancestral mothers were living only a few miles apart in north County Galway is still meaningful.

I emailed the match twice, several months apart, and haven’t heard back. That’s not at all unusual in genetic genealogy. People test, get their results, and then move on. In the meantime, I decided to build out their female tree line using the information provided in the match’s account profile and available historical information and records, which only deepened my sense that this connection is real, even if it remains just out of reach. I didn’t advance my family tree, but I am okay with that. This update provided valuable new information.

As if that weren’t exciting enough, there’s one more detail to this mitochondrial journey that I find amazing. FTDNA also connects one’s mtDNA results to ancient DNA samples from archaeological burial sites. My mtDNA links to tested samples from two prehistoric men from Ireland, one of whom is known as “Carrowkeel Man 532,” who was buried in County Sligo thousands of years ago.2 The location is only about 82 miles north of Belclare, about a 2-hour car drive away. This bit of information suggests that my maternal line ancestors may have lived in the west of Ireland for a very, very long time, and it links genealogy to the sphere of deep human history. How fascinating and fun!

If you haven’t yet explored your aDNA or mtDNA, why not? If you tested a while ago and haven’t revisited your results since last year’s mitotree update, I’d encourage you to take a peek at the updated results. You, too, may find an interesting match just waiting for you to pick it up. If you’ve been on the fence about DNA testing because of the cost, FTDNA often runs holiday sales. St. Patrick’s Day is just a few weeks away, and Mother’s Day is coming soon after it. Maybe there will be a sale. Either holiday would be a wonderful occasion to give the gift of DNA testing to learn more about your heritage and your ancestral mothers. Treat your mother, treat yourself, or do testing together!

Here’s the link to their site: FamilyTreeDNA

Thank you for reading.

♥︎ Krista

Feature Photo: FTDNA website

—

Footnotes

- I purchased some DNA kits in late 2011, and the results were populated in early 2012. The processing time was about three months. ↩︎

- Carrowkeel Man 532 lived during the Late Neolithic Age. His burial site was in the passage tomb of Cairn K, located at the top of Carrowkeel Mountain, near the N4 highway south of Sligo town, in County Sligo, Ireland. The other prehistoric mtDNA sample match was with Millin Bay 6 man, who lived in the Early Neolithic period. His remains were found in a Cairn at Millin Bay, on the southern tip of the Ards Peninsula in County Down. This archaeological site is on the shore of the Irish Sea. Check out the YT video “A Game of Bones” presented by Pádraig Meehan and posted by the Office of Public Works, Ireland, to learn a little about the connections between Carrowkeel Man 532 and Millin Bay 6 man. As more ancient Irish remains are tested, the prehistoric human story of Ireland becomes clearer. ↩︎