In the last story web post, Iron Roads and Irish Labor: Building Maine’s Railroad, I shared information about some of the accidents and deaths of Irish immigrant laborers who built Maine’s growing railroad system. This story adds to it by following the lives of some other men who labored on Maine’s Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad. Their stories are of exploitation and longing, and of their will to persevere in the face of hardship.

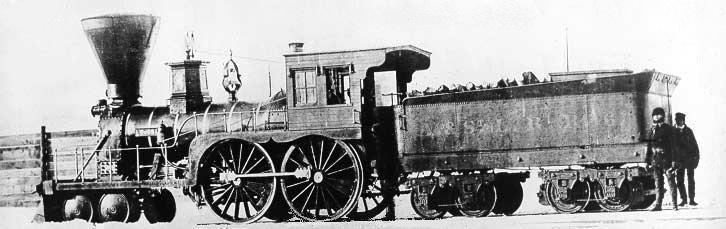

In the mid-1840s, the Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad began its push through the forested hills of western Maine, laying down the miles and miles of iron roads that would connect Portland to Montreal. This ambitious project was but one of many railroad developments occurring in America at the time.1 Yet for the countless thousands of Irish immigrant men who helped build America’s railroad infrastructure, the experience was often marked by hardship, injustice, and tragedy.

The timing of construction could not have been more opportune. Across the Atlantic, Ireland was gripped by the Great Hunger. Between 1845 and 1852, famine and disease devastated the island, forcing millions of people to emigrate. 2 Many sought refuge and work in America, where they contributed to the country’s impressive transportation infrastructure boom by digging canals, building granite rail bridges, and laying down the iron rail tracks.

Railroad companies needed workers. Prominent businessmen and contractors, such as John M. Wood, placed newspaper advertisements seeking to recruit 500 to 1,000 laborers at a time with the promise of a dollar a day to work on the railroad. The destitute and unskilled Irish immigrants, fresh off the boat from a starving homeland, eagerly took up the offer. But the promise was not all that it had seemed. Laborers’ wages were sometimes withheld or delayed. Laborers on the Atlantic and St Lawrence Railroad jobs would soon learn they would receive only 75 cents a day, a quarter less than promised. The workers lived in makeshift shanties at the job sites, exposed to illness and harsh weather, including rain, snow, and freezing temperatures. At this time, it was a bit cooler than it is today because the northern hemisphere was still emerging from a mini ice age! In the winter months, temperatures plunged, and snow piled up to several feet deep. 3 Laborers endured hazardous work conditions where accidents and fatalities were the norm, including from falling rocks and collapsing embankments.

The contractors overseeing the early sections of the Atlantic and St. Lawrence line, “John G. Mires” and “Mager Hall,” became known for their exploitation. A news report published in the Boston Pilot on May 15, 1847, under the title “Injustice to Laborers,” exposed their abuse, stating that these businessmen “seduced and enticed a great number of Irishmen from the city of New York to come out here at a dollar a day, and at the end of the month, to deduct $7.33 from their miserable wages.” When the Maine Irish immigrant railroad laborers demanded the pay they were owed, contractors threatened to replace them with “three hundred starving Irish now landing in New York and Boston, that would be glad to get their grub.”4

Yet even amid such injustice, these men kept working, and they sought to build a sense of community. Some Irish immigrant men employed on the Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad placed “Information Wanted” advertisements in the Boston Pilot, a Boston, Massachusetts-based newspaper, seeking their lost relatives who had also crossed the Atlantic. These notices spoke of loneliness and longing, but also the belief that their family ties could make a difference in their daily lives, in this strange, new world. Brothers James and Peter Mulvy, who were at the Mechanic Falls, Maine, railroad site, were in search of their brother, Michael.5 Their advertisement was published on May 5, 1849. Michael Donnelly, working on the Danville, Maine, section of the railroad, placed an ad on April 22, 1848, seeking his brother, Thomas, whom he had last seen in Pictou, Nova Scotia. The Donnelly brothers had emigrated from the townland of Ballyfeeny, in Brumlin, County Roscommon, Ireland.6 Their pleas for news of family reflect the experiences of countless others whose journeys scattered kin across the continent and the longing for closeness.

This story offers further examples of the Irish immigrant railroad laborer experience in mid-19th-century Maine and elsewhere in America. They arrived in this new land with little to nothing, and they were often met with exploitation and hardship. So, let us remember their contributions and sacrifices that helped lay the foundations of communities, industries, and connections that endure in America to this day. The rails they built in this great country were their pathway toward a better life than what was left behind in the old country. The iron roads were built with a spirit that refused to let hardship have the final say in their lives.

Thank you for reading this story.

♥︎ Krista

– – – – – – – – –

Notes

- Kenny, Bill. A History of Maine Railroads. History Press, 2020. 66-68. ↩︎

- Miller, Kerby A, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America. Oxford University Press, 1985. ↩︎

- Smith College. “The Effects of the Little Ice Age.” Accessed October 26, 2025. https://www.science.smith.edu/climatelit/the-effects-of-the-little-ice-age. ↩︎

- “Injustice to Laborers.” Boston Pilot. May 15, 1847. Vol. 10, no. 20. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=bpilott18470515-01.2.21&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22Injustice+to+laborers%22—— ↩︎

- “Information Wanted: Of Michael Mulvy.” Boston Pilot, May 5, 1849, vol. 12, no. 18. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=bpilott18490505-01.2.17.3&srpos=4&e=——184-en-20–1–txt-txIN-mechanic+falls——. ↩︎

- “Information Wanted: Of Thomas Donnelly.” Boston Pilot, April 22, 1848. Vol. XI, no. 17. Accessed October 20, 2025. https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=bpilott18480422-01.2.14.4&srpos=5&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-Michael+donnelly%2C+pictou——. ↩︎

Leave a comment